A presentation at the Collision Industry Conference (CIC) earlier this year included a number of examples of vehicle repairs that could easily be done incorrectly if a technician makes presumptions about the process based on past experience rather than carefully following the OEM procedures.

Scott VanHulle, manager of I-CAR's Repairability Technical Support and OEM Technical Relations, cited a Silverado box side installed at the factory with 10 welds.

“In the repair, you’re only putting seven in,” VanHulle said. “Where those three extra welds were, they want you to put crash-toughened adhesive in there. If you were to get to this point and only then realize you need to have crash-toughened adhesive, you’re going to have to remove that part that you already have partially installed because there’s no way to get the adhesive in there.”

Jason Bartanen of Collision Hub pointed to something similar with the lower outer rail on the Chevrolet Bolt.

“It’s attached [at the factory] with spot welds and MIG-brazed joints, essentially,” Bartanen said. “But when you do the replacement procedure, there’s adhesive, spot-welding, weld-bonding, rivets, rivet-bonding, plug welds and MIG-brazing. Seven different attachment methods on that one part that came from the factory with two attachment methods. So making an assumption that you know what you’re doing because you’ve been doing it for a long time is a very dangerous assumption to make.”

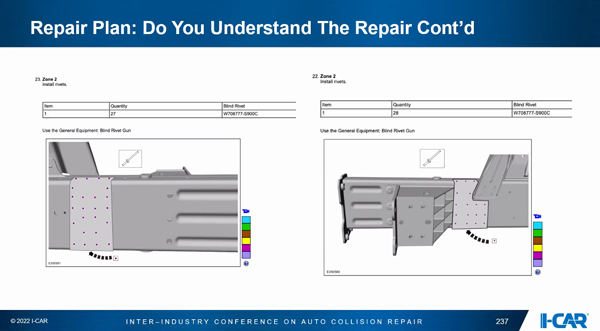

VanHulle also shared slides related to a sectioning procedures for a front lower rail on a Ford Explorer. One slide of the procedure he shared calls for MIG welding.

But in addition, he said, depending on which of two zones is being repaired, “you actually have to make these panels out of the service part that you have to rivet bond over the top of the area you just welded. So when you’re doing the repair planning, if you just quickly go through that procedure, you might think, ‘Oh we just need to weld it.’ Well, no, you have to make these parts. You have to do the rivets. So if you’re not truly understanding the procedure, and have those rivets in-stock, there’s no way the technician is going to know what to do, and he’s going to make a mistake or only do part of it.”

VanHulle said another example of the increased use of adhesives by automakers can be seen in I-CAR’s free 51-minute “Repairers Realm” video on the roof replacement procedure for the 2022 Honda Civic.

“The procedure is interesting, but if you don’t do the proper planning, and have the proper pieces in place, there’s no way you’re going to put that roof on correctly, especially if you’re assuming it was like the last Honda you did,” VanHulle said. “And this is not just happening with one automaker. All of them are having adhesives show up pretty much everywhere.”

The presentation at CIC was similar to a message from American Honda last fall about making repair presumption. Scott Kaboos, assistant manager of collision repair training and technology for American Honda, said students at Honda’s hands-on training facility in Illinois are often surprised the ADAS cameras on one model year Accord will require different targets and processes than those on another.

“Even within Honda and Acura, we have so many different systems, so many different calibrations,” Kaboos said. “There is no one standard way [across models] even within our own company.”

It highlights the need to always check the automaker’s repair procedures for each particular vehicle. Kaboos said a student in one of his classes last fall told him he’d used an aftermarket scan tool on a 2017 Honda Odyssey, and followed that software’s recommendation to use a certain target and to put the camera into calibration mode.

“He did that, and fried the camera,” Kaboos said, acknowledging he had to look up the reason why. “It turned out it was a dynamic-only camera. So it allowed it to go into [calibration mode], but then it went into a spiral loop, and would never come out of that function because it wasn’t designed to do a static calibration. He ended up having to buy an $800 camera and get it dynamically calibrated [to get the vehicle] back to the customer.”

John Yoswick